You may remember where you where when Mt. St. Helens erupted but until you visit the site, you can not comprehend the magnitude of the blast. Most of the words in this post are from the Volcano Review, a park visitor guide. The mountain lost 1300' of height and 0.67 cubic miles of total volume.

You may remember where you where when Mt. St. Helens erupted but until you visit the site, you can not comprehend the magnitude of the blast. Most of the words in this post are from the Volcano Review, a park visitor guide. The mountain lost 1300' of height and 0.67 cubic miles of total volume.

Here's what Mt. St. Helens looked like before May 18, 1980.

Here's what Mt. St. Helens looked like before May 18, 1980. The following is a sequence of photos as the eruption occured. Starting in March of 1980 there were lots of earthquakes under the volcano and a small vent formed.

The following is a sequence of photos as the eruption occured. Starting in March of 1980 there were lots of earthquakes under the volcano and a small vent formed. At 8:32 a.m. the north face of the mountain began to slide downhill.

At 8:32 a.m. the north face of the mountain began to slide downhill. The eruption began with a massive landslide (debris avalanche) that buried 14 miles of river valley to an average depth of 150'.

The eruption began with a massive landslide (debris avalanche) that buried 14 miles of river valley to an average depth of 150'.

The landslide released trapped magma and gas, producing a sideways explosion (lateral blast) of hot rocks and ash killing trees up to 17 miles north of the volcano.

The eruption leveled 230 square miles of forest in less than 10 minutes.

A vertial ash eruption rose to a height of 15 miles above the crater and continued for 9 hours. Ash drifted to the northeast.

A vertial ash eruption rose to a height of 15 miles above the crater and continued for 9 hours. Ash drifted to the northeast.

Cement-like slurries of glacial melt water and boulders called lahars scoured and buried streams draining the volcano. Fiery avalanches of pumice and hot gasses called pyroclastic flows flowed into the valley north of the crater.

Fifty-seven people died because of the eruption. One of the most memorable was a man called Harry R. Truman who had a lodge on Spirit Lake. He refused to leave and stayed with his 16 cats. He did not survive. Others were NFS volcano watchers or people not in the restricted area around the volcano. The mudflows down the river valleys swept away homes.

The massive landslide that triggered the eruption buried 14 miles of river valley and created 150 new lakes, ponds and wetlands. This new habitat has powered a rapid resurgence of life - creating the most biologically-rich landscape in the monument. It is home to a diverse array of amphibians, birds, insects and at least 140 plant species.

Predators such as hawks, owls, coyotes, bobcats and weasels search the 230 square mile blast area for small mammals. Small mammals play a vital role in ecosystem recovery by feeding on plants, creating burrows, dispersing seeds and concentrating nutrients in their droppings.

Predators such as hawks, owls, coyotes, bobcats and weasels search the 230 square mile blast area for small mammals. Small mammals play a vital role in ecosystem recovery by feeding on plants, creating burrows, dispersing seeds and concentrating nutrients in their droppings.

Fish populations rapidly rebounded in steep mountain streams that were smothered by volcanic ash. Rapidly flowing water flushed ash from channels exposing cobbles and gravels that are important for spawning and aquatic insects -- a primary food source. Fish have also benefited from pools and riffles formed by blown-down trees and pleantiful food in the open sunny, blast area.

Fish populations rapidly rebounded in steep mountain streams that were smothered by volcanic ash. Rapidly flowing water flushed ash from channels exposing cobbles and gravels that are important for spawning and aquatic insects -- a primary food source. Fish have also benefited from pools and riffles formed by blown-down trees and pleantiful food in the open sunny, blast area.

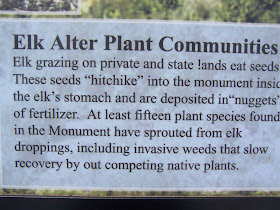

Large herbivores like elk and deer are modifying plant communities around the volcano. By selectively and heavily over browsing some plant species verses others, and through their trampling and ground disturbance, elk are profoundly influencing plant succession at Mount St. Helens.

Large herbivores like elk and deer are modifying plant communities around the volcano. By selectively and heavily over browsing some plant species verses others, and through their trampling and ground disturbance, elk are profoundly influencing plant succession at Mount St. Helens.

This is the Blast Zone.

This is the Blast Zone.

Although the blast area is untouched by humans as an experiment to see how nature recovers on its own, much of the rest of the land affected by the eruption was owned and used by lumber companies.

Although the blast area is untouched by humans as an experiment to see how nature recovers on its own, much of the rest of the land affected by the eruption was owned and used by lumber companies.

Mt. St. Helens and the river valley from the Forest Learning Center parking lot.

Mt. St. Helens and the river valley from the Forest Learning Center parking lot.

No comments:

Post a Comment